Swearing to tell a lie

It was a giant step for Deirdre Jones to take the witness stand that day in 2012. She had returned to a Philadelphia courtroom to testify about a 1991 murder near Rittenhouse Square. Her first time on the stand, she said, haunted her for almost two decades.

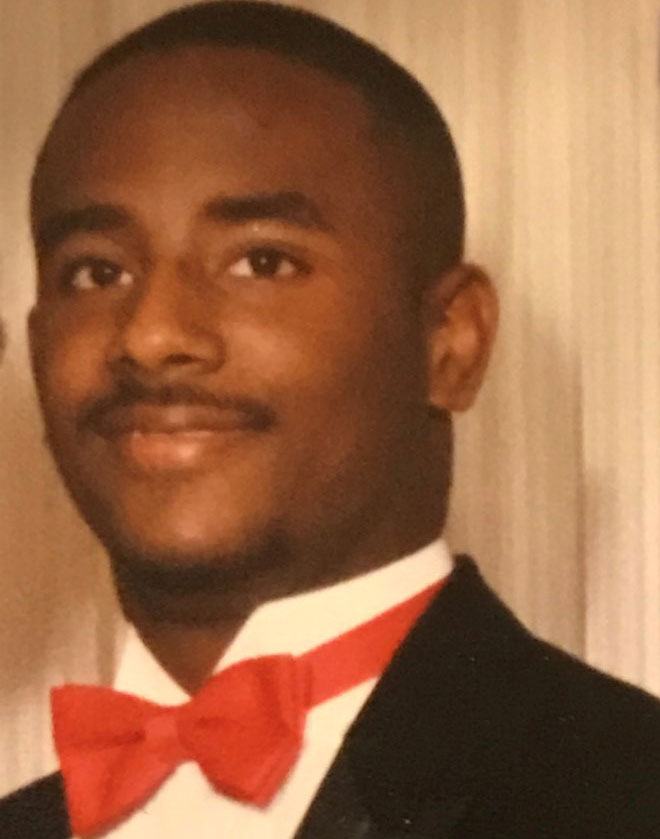

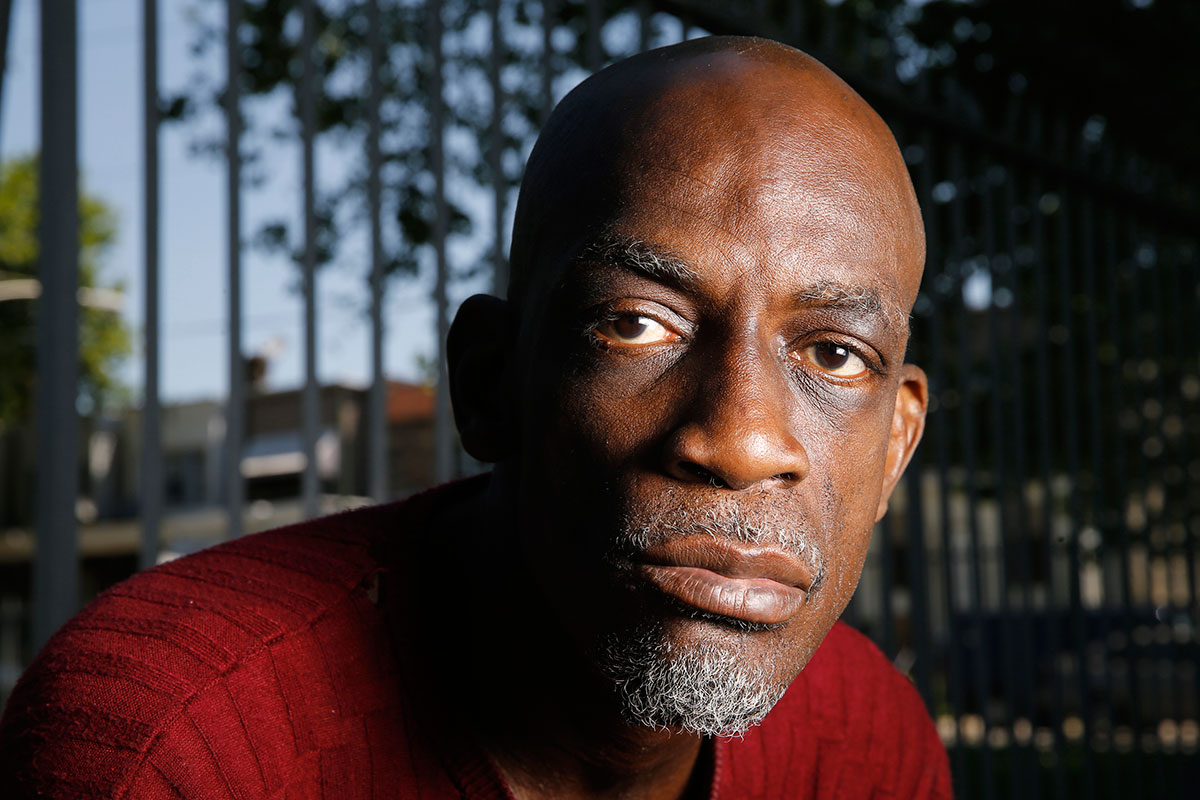

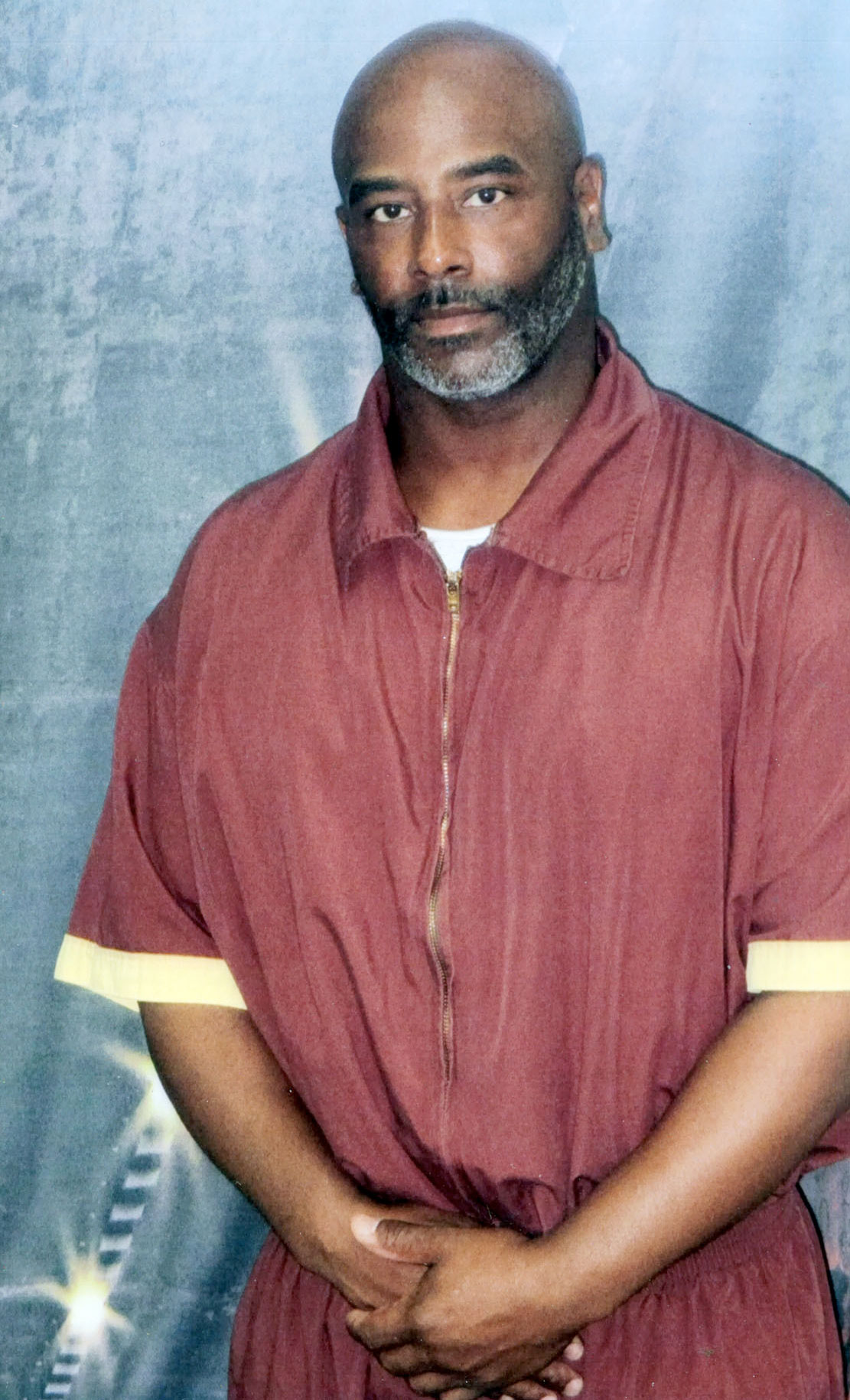

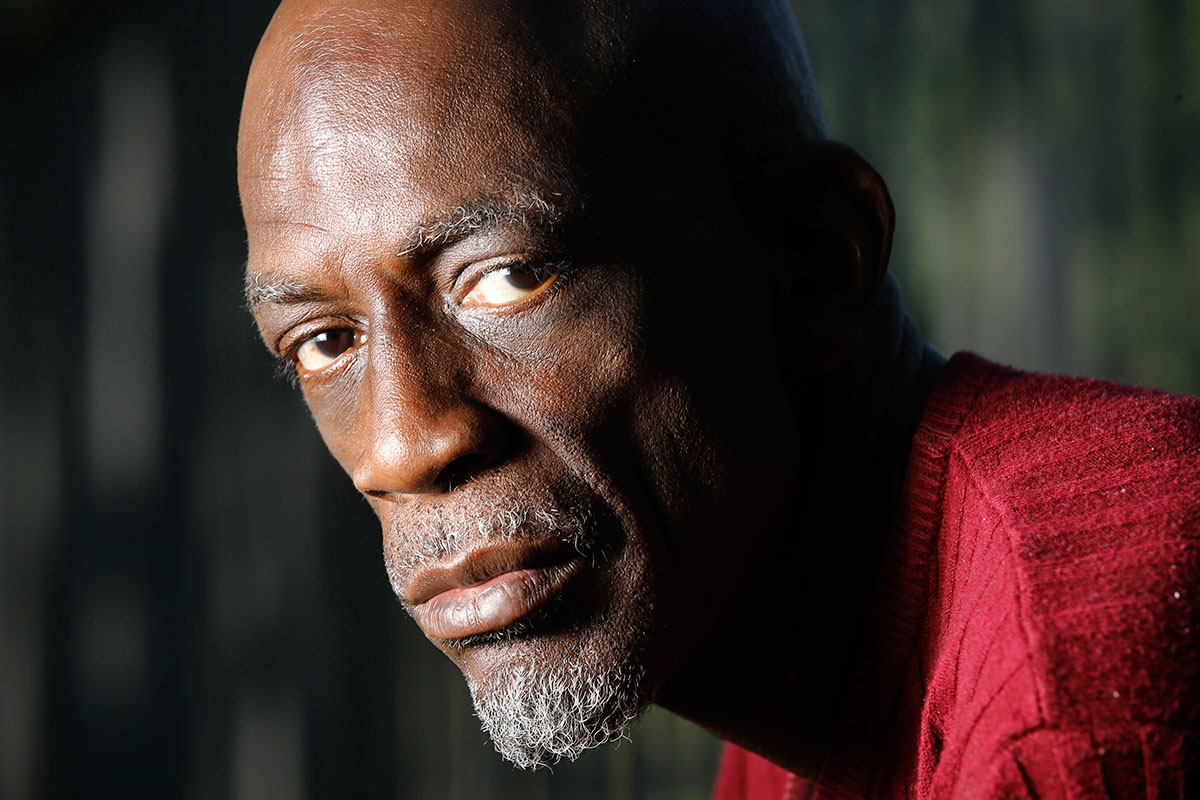

Jones had been the star witness in the 1993 trial of Chester Hollman III, charged with killing a University of Pennsylvania student. Hollman, a 21-year-old with no criminal history, had been picked up minutes after the murder and blocks from the scene.

Detectives found no physical evidence tying him to the crime. So Jones’ testimony — that she had been riding with Hollman and another man in an SUV when they got out and she heard a gunshot — almost certainly cemented his conviction and life prison sentence.

But when Hollman’s appeals lawyers called her back to the witness stand 19 years later, Jones offered a different account.

Choking up, Jones swore she had lied at trial, that she and Hollman had been driving alone that night and he had no role in the killing of the victim, Tae-Jung Ho. Jones said detectives coerced her into implicating Hollman.

Helping to lock him up, she said, stoked years of depression.

“I just thought it was time for me to come out and to tell the truth,” Jones, then a 40-year-old hospital worker, testified in January 2012. “Maybe some of my depression would go away.”

The case illustrates a stark reality of the criminal justice system: People lie. They lie to stay out of jail, to get out of jail, to curry favor with cops. And police sometimes lie, too. It’s so common, so understood within the court system, that regulars have a name for it: Testilying — when officers lie to buttress a weak case, or when a defendant lies in hopes of winning an acquittal.

In the end, Philadelphia Common Pleas Judge Gwendolyn N. Bright followed a long line of judges who reject witness recantations as unreliable. She did not believe Jones’ new testimony and denied Hollman’s motion to reopen his case.

Jones wasn’t the first witness to claim to have lied at the trial. A decade before she came forward, Andre Dawkins — the only other person to place Hollman at the murder scene — swore police also had pressured him to falsely implicate Hollman.

The twists and turns of the case show how difficult it is to figure out who is lying — and when.

If Jones testified truthfully in 1993 but lied on the stand five years ago, she risked a perjury charge. If her more recent testimony was true, then David Baker, the former Philadelphia detective who interviewed her after the murder, lied in 2012 when, under oath, he flatly denied her accusations.

Untangling who is lying in criminal cases can be “absolutely daunting,” said lawyer Richard L. Scheff, who recalled wrestling with the issue when he was a federal prosecutor. "There can be any number of reasons why people change their statements."

Scientific advances in crime solving — especially DNA testing — have freed the wrongfully convicted and proven guilt. Almost as a rule, experts say, courts don’t like to reopen old cases without compelling scientific evidence.

That is especially problematic in prosecutions built on the testimony of witnesses. Like Hollman’s.

The Philadelphia District Attorney’s Office declined to discuss Hollman’s case. His current appeals lawyer, Alan Tauber, said he plans to ask prosecutors for a new review.

Jennifer Creed Selber, former chief of the office’s homicide unit, acknowledged witness recantations are a “pervasive” problem. She believes witnesses usually recant because they fear retaliation from defendants.

“If we attempted to prosecute every witness that perjures themselves,” said Selber, “it would be a completely unworkable and impossible situation.”

If the verdict in the Hollman case is accurate, one participant has been lying consistently since 1991: Hollman has never stopped saying he is innocent.

Pressure on police, witnesses

Five years ago, the University of Michigan Law School and the Center on Wrongful Convictions at Northwestern University's law school started a database of criminal exonerations since 1989. The National Registry of Exonerations has catalogued over 2,000 cases.

DNA evidence spurred many, but the growing number of exonerations has led to a “profound change” in the perception of convictions, said Samuel Gross, senior editor of the registry.

“What the DNA cases showed everybody,” he said, “is that a lot of criminal convictions that no one had thought to think about were wrong.”

More than half of his registry’s cases involve perjury and/or false accusations.

Much lying stems from misconduct by police and prosecutors desperate to solve crimes, researchers say. “Witnesses are pressured, threatened, subjected to violence, offered secret deals such as reduced charges in the case at hand or for other crimes, or otherwise coerced or persuaded to falsely accuse the defendant,” a 2013 registry report concluded.

James McCloskey, the founder of Centurion Ministries, a New Jersey-based organization that has helped exonerate more than 50 prisoners since 1980, said about three dozen witnesses have recanted their testimony in Centurion cases.

“They want to reconcile themselves, really help right a terrible wrong,” McCloskey said, but they fear getting in trouble. It can take years to get a witness to publicly acknowledge the lie — and then additional years to actually win an exoneration.

Fernando Bermudez spent nearly two decades in a New York prison before being cleared of the 1991 murder of a teen in Greenwich Village, despite recantations from all five eyewitnesses against him two years after the shooting. A judge later decided to throw out the charges because of the recantations and police misconduct.

Jose Medina, who is serving life for the 1991 killing of a Philadelphia police officer’s brother, is waiting for the new trial he was granted in 2011 after a prosecution witness admitted lying under oath.

Don Ray Adams Jr., a Philadelphia barber, was exonerated in 2011 — 21 years into a life sentence for murder — after the key witness against him recanted. A convicted felon and crack cocaine addict who said she had turned her life around contacted Adams’ lawyer in 2007. She said police pressured her to lie and say Adams was the man who shot two others during a drug deal. Adams won a new trial. A jury acquitted him.

Exonerated After False Testimony

Six local cases of men who were convicted of murder and other charges in part because of false testimony, only to be later exonerated. The six spent a combined 107 years in prison.

The year of that double murder, 1990, Philadelphia recorded 500 homicides, a high mark in at least a half-century.

Experts say such rising crime can spur a spike in witness intimidation.

If there is a “significant uptick in crime,” said Christopher Slobogin, a Vanderbilt University criminal law professor, “there’s going to be more pressure on police to put pressure on witnesses.”

The year Chester Hollman was arrested, Philadelphia logged 444 homicides. By late August 1991, detectives were scrambling to solve two or three killings a day.

Tae-Jung Ho was victim 301.

A killing on 22nd Street

Ho, a 24-year-old South Korean, was enrolled in an English program at the University of Pennsylvania. He was walking on 22nd Street, between Chestnut and Walnut Streets, at 1 a.m. on Tuesday, Aug. 20, when two men approached. One held him down while the other shot him in the chest. It is unclear whether anything was taken. Police found $99 in Ho’s wallet.

Junko Nihei, a 20-year-old Pennsylvania Ballet student walking with Ho, said the shooter wore a blue hooded shirt or jacket and his accomplice — whom prosecutors later alleged was Hollman — wore a dark baseball cap and “perhaps reddish color” shorts.

The 911 calls began at 1:01 a.m.

One witness said she saw three black men and one brown-skinned woman in or near a van or Jeep. Another said he saw two black teenagers and a white Chevrolet Blazer with a female with a “medium complexion” at the wheel.

Taxi driver John Henderson said he was driving on 22nd Street when he saw a flash, then a man in a blue hoodie get into a white vehicle on Chestnut Street. Henderson told police four people were inside the SUV — and he followed the vehicle for about seven blocks until he lost it. He gave police a partial tag: YZA.

At 1:05 a.m., police pulled over a white Chevrolet Blazer with a license plate starting with YZA near 22nd and Locust, about six blocks from the shooting. Hollman was driving; Jones sat in the passenger seat.

Hollman was wearing a black baseball cap and aqua pants, according to trial testimony. Police said they saw red spots on his pants that looked like blood.

“I did what I had to do to survive”

Andre Dawkins had been hanging out at a gas station when a shot rang out a block away. He claimed to have seen Hollman at the scene.

“No ifs, ands, or buts: I can never forget his face after something like that,” Dawkins testified at trial.

Dawkins also acknowledged at trial he had been treated for mental illness. He has a history of schizophrenia, medical records show.

A decade after the trial, after a private investigator hired by Hollman’s appeals lawyers tracked him down, Dawkins said his testimony had been a lie. He said he had an outstanding burglary charge back in 1991 and police, including Det. Raleigh Witcher, threatened him.

“They told me if I did not say it was [Hollman], I was going to jail,” Dawkins said in an interview with the Inquirer. “I did what I had to do to survive.”

(Witcher is now dead.)

Back then, Dawkins said, he was too high on drugs to recall what he saw. His role in convicting Hollman is one of his biggest regrets.

“There’s no way possible that I could go to my grave knowing that I put a man in jail and I don’t know he did a crime,” he said.

Dawkins’ testimony had already come under scrutiny. Five years after the trial, a federal appeals court considering an appeal from Hollman had concluded Dawkins had indeed lied on the witness stand — not about seeing the defendant but about his own long criminal record. Still, the three-judge panel said it wasn’t enough to reopen the case, pointing to other damning proof of Hollman’s guilt.

"Compelling evidence," Judge Marjorie Rendell wrote in the opinion, "was provided by Deirdre Jones.”

Confused and frightened

Then 20, Jones had been living in the same North Philadelphia apartment complex as Hollman on that August 1991 night. She was bored when she saw him around midnight; Hollman asked if she wanted to take a ride.

They drove into Center City in a rented white Blazer. She said she didn’t have her glasses and wasn’t paying attention to where they had been driving — until police pulled them over.

The account she later gave at trial mirrored the statement she signed at police headquarters: Jones told jurors she had been in the vehicle with Hollman and another man and woman, strangers to her. Hollman and the man said they were going to “get somebody,” then left the vehicle, Jones testified. She heard a gunshot, then they returned and sped off. The other woman and man got out soon after.

Jones now says that testimony was a lie.

Both in the 2012 hearing and in interviews with the Inquirer, Jones said she had been scared that night; she had never before been in custody. She kept telling detectives she didn’t know anything about a shooting, she says, but they accused her of lying. They told her Hollman had confessed — and that she had better cooperate.

“They said if I didn’t, I was going to get locked up, they was going to charge me also,” Jones told the Inquirer.

Jones said she became confused and frightened — especially after investigators told her Hollman had mob ties — so she agreed to sign the statement Det. David Baker typed.

“I was terrified,” she said.

In fact, Hollman, who at the time worked as an armored car driver, had not confessed, and no evidence linked him to any violent group. (Courts have held that police may lie to suspects and potential witnesses in solving crimes.)

Jones signed her nine-page statement by 7 a.m., at least four-and-a-half hours after detectives began questioning her. She said police also told her she should be concerned for her safety. So, hours later, Jones grabbed her two small children, boarded a plane, and relocated to her grandmother’s home in Georgia, where she would remain, in fear, for the next few years. She said authorities paid to fly her back for Hollman’s preliminary hearing and trial.

When she testified in 2012, Jones said she felt bad about lying decades ago and had thought more than once about publicly recanting but had been frightened she would be charged.

“Chester was in [prison] all that long time because I was scared to come forward and say anything,” Jones testified. “If it was – if it was now, it would be different. Chester wouldn’t be in there today, because I would not be afraid to say we was not there.”

“The job is to get to the truth as close as you can”

Baker, the detective, disputed Jones' account. Taking the witness stand after her in 2012, he essentially told Judge Bright that Jones had told the truth in 1993 but was lying to her – both about that August night and her accusations of police coercion during her interrogation.

“I believe she at first said she didn't know what I was talking about, and then she admitted that she was only in the car, and then she said she was looking out for police,” Baker testified. “I don’t think she really thought she was involved until she thought about it.”

Baker retired in 2012. In a phone interview last month from his Florida home, he insisted he didn’t lie to Jones in 1991 or to the judge two decades later. He said other detectives may have told Jones that Hollman was dangerous or had confessed, but that his role was just to take down the statement as she recited it, which he did.

“Is that true or not? I don’t know," Baker told the Inquirer. “The job is to get to the truth as close as you can.”

Baker is one of 11 former homicide detectives named as defendants in a federal civil-rights lawsuit filed in September. They are accused of pressuring suspects to confess and intimidating witnesses to implicate suspects. Baker bristled at his inclusion in the lawsuit and denied any wrongdoing.

"Disbelief and hurt"

Hollman, now 47, is one of more than 5,400 people serving life sentences in Pennsylvania.

In an interview at a state prison near Wilkes-Barre, he repeated what he has maintained since 1991 – that he had nothing to do with the shooting.

Hollman said he and Jones were headed to Southwest Philadelphia that night to visit one of his friends. They drove down Broad Street and turned onto Lombard Street when the police pulled him over.

Hollman said he's never been angry with Jones because he believes she had been pressured by police. "It was never anger," he said. "Just disbelief and hurt."

He said his first lawyer, A. Charles Peruto Sr., a legendary defense lawyer who died in 2013, advised him to accept a plea offer for a five-to-10-year sentence. Hollman said he insisted on a trial; he always believed police and prosecutors would eventually realize he had been in the wrong place at the wrong time.

The lawyer who represented him during the seven-day 1993 trial, Gerald Stein, highlighted for jurors the lack of physical evidence. No murder weapon was found. Even the red stains on Hollman’s pants were proven not to be blood, tests showed.

Stein reminded jurors that sometime after Hollman’s arrest, investigators showed Dawkins a photo of a Philadelphia woman who had rented another white Blazer with a YZA plate from the same rental agency — and that SUV was returned at 5 a.m. one day after the shooting. Dawkins even had told police she looked like the same woman he saw behind the wheel of the SUV at the murder scene.

But it’s unclear if detectives ever questioned that woman. Neither prosecutors nor the defense called her at the trial. Attempts by the Inquirer to locate her have been unsuccessful.

Hollman said he wanted to testify, but Stein advised against it because of the likelihood of an aggressive cross-examination by prosecutor Roger King, whose courtroom skills were renowned. (Stein has declined to comment; King died last year.)

Hollman said he was crushed by the guilty verdict, which carried a mandatory life term, especially when he turned around and saw his mother’s pained expression. She died years later, and he could not attend her funeral.

He said he is buoyed by the love and support of his father and sister, who have always believed he is telling the truth.

Years after his conviction, he said, a prosecutor and Witcher visited him in prison, offering to help him in exchange for the name of the shooter. Hollman said he wished he could help, but he had no idea who the shooter was.

His current lawyer, Tauber, verified that prison visit.

Hollman said he spends his days watching TV, working in the prison gym, and clinging to a one-day-at-a-time attitude, hoping he will eventually be released.

“I just never believed,” he said, “it was going to be forever.”

Exonerations since 1989 that involved false testimony from witnesses, police, or prosecutors

Since 1989, there have been more than one thousand exonerations involving witnesses - and police - that perjured themselves. Scroll through and search these cases below. Those highlighted blue indicate police officer perjury.

| Name | Age | Race | Sex | Prison Loc. | Crime | Convicted | Exonerated |

|---|

Name | Age | Race | Sex | Prison Loc. | Crime | Convicted | Exonerated |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. Jabir Nash | 39 | Black | Male | New Jersey | Child Sex Abuse | 2002 | 2013 |

| Aaron Galli | 22 | Caucasian | Male | Utah | Murder | 1993 | 1993 |

| Aaron Patterson | 21 | Black | Male | Illinois | Murder | 1989 | 2003 |

| Abdel-Ilah Elmardoudi | 35 | Other | Male | Fed-MI | Supporting Terrorism | 2003 | 2004 |

| Ada JoAnn Taylor | 21 | Caucasian | Female | Nebraska | Murder | 1989 | 2009 |

| Adam Bradley | 48 | Caucasian | Male | New York | Assault | 2010 | 2013 |

| Adam Miranda | 21 | Hispanic | Male | California | Murder | 1983 | 2009 |

| Adam Tatum | 36 | Black | Male | Tennessee | Assault | 2012 | 2013 |

| Adolph Munson | 37 | Black | Male | Oklahoma | Murder | 1985 | 1995 |

| Ahmed Hannan | 32 | Other | Male | Fed-MI | Fraud | 2003 | 2004 |

| Alan Gell | 20 | Caucasian | Male | North Carolina | Murder | 1998 | 2004 |

| Albert Algarin | 21 | Hispanic | Male | New York | Child Sex Abuse | 1985 | 1990 |

| Albert Burrell | 30 | Caucasian | Male | Louisiana | Murder | 1987 | 2001 |

| Albert Curry | 53 | Black | Male | Fed-SD | Sexual Assault | 2002 | 2003 |

| Albert Daidone | 38 | Caucasian | Male | Pennsylvania | Murder | 1984 | 1999 |

| Albert Luster | 18 | Black | Male | Wisconsin | Child Sex Abuse | 1990 | 1992 |

| Albert Mitchel | 42 | Black | Male | New York | Drug Possession or Sale | 2007 | 2008 |

| Alberto Ramos | 21 | Hispanic | Male | New York | Child Sex Abuse | 1985 | 1994 |

| Alberto Sifuentes | 22 | Hispanic | Male | Texas | Murder | 1998 | 2008 |

| Alejandro Hernandez | 19 | Hispanic | Male | Illinois | Murder | 1985 | 1995 |

| Alfred Brown | 21 | Black | Male | Texas | Murder | 2005 | 2015 |

| Alfred Rivera | 25 | Hispanic | Male | North Carolina | Murder | 1997 | 1999 |

| Alfred Williams | 53 | Black | Male | Texas | Drug Possession or Sale | 1987 | 1989 |

| Alfredo Vargas | 62 | Hispanic | Male | Connecticut | Child Sex Abuse | 2002 | 2006 |

| Algie Crivens | 18 | Black | Male | Illinois | Murder | 1992 | 2000 |

| Ali Tuckett | 36 | Black | Male | New York | Child Sex Abuse | 2011 | 2016 |

| Alprentiss Nash | 20 | Black | Male | Illinois | Murder | 1997 | 2012 |

| Alstory Simon | 32 | Black | Male | Illinois | Murder | 1999 | 2014 |

| Alton Logan | 28 | Black | Male | Illinois | Murder | 1982 | 2008 |

| Alvena Jennette | 21 | Black | Male | New York | Murder | 1988 | 2014 |

| Alvin McCuan | 28 | Caucasian | Male | California | Child Sex Abuse | 1984 | 1996 |

| Amaury Villalobos | 30 | Hispanic | Male | New York | Murder | 1981 | 2015 |

| Amine Baba-Ali | 31 | Other | Male | New York | Child Sex Abuse | 1989 | 1992 |

| Andre Davis | 19 | Black | Male | Illinois | Murder | 1981 | 2012 |

| Andre Ellis | 35 | Black | Male | Alabama | Sexual Assault | 2013 | 2014 |

| Andre Hatchett | 24 | Black | Male | New York | Murder | 1992 | 2016 |

| Andre Minnitt | 21 | Black | Male | Arizona | Murder | 1993 | 2002 |

| Andre Taylor | Black | Male | California | Attempted Murder | 1990 | 1998 | |

| Andrew Craig | 24 | Black | Male | Massachusetts | Assault | 2005 | 2006 |

| Andrew Johnson | 39 | Black | Male | Wyoming | Sexual Assault | 1989 | 2013 |

| Andrew Kayachith | 19 | Asian | Male | Fed-TN | Other Violent Felony | 2012 | 2016 |

| Andrew Taylor | 25 | Black | Male | Florida | Child Sex Abuse | 1991 | 2016 |

| Angel M. DeAngelo | 26 | Hispanic | Male | Fed-NY | Murder | 2003 | 2004 |

| Angel Rodriguez | Hispanic | Male | Illinois | Murder | 1998 | 2000 | |

| Angel Toro | 30 | Caucasian | Male | Massachusetts | Murder | 1983 | 2004 |

| Angelo Martinez | 19 | Hispanic | Male | New York | Murder | 1986 | 2002 |

| Ann Shepard | 33 | Caucasian | Female | North Carolina | Other Violent Felony | 1972 | 2012 |

| Anna Vasquez | 19 | Hispanic | Female | Texas | Child Sex Abuse | 1998 | 2016 |

| Anthony Adams | 26 | Hispanic | Male | California | Manslaughter | 1996 | 2001 |

| Anthony Bragdon | 19 | Black | Male | District of Columbia | Sexual Assault | 1992 | 2003 |

| Anthony Cooper | 24 | Caucasian | Male | Oklahoma | Child Sex Abuse | 1995 | 1999 |

| Anthony Davis | 20 | Caucasian | Male | Iowa | Sexual Assault | 1990 | 1992 |

| Anthony DiPippo | 18 | Caucasian | Male | New York | Murder | 1997 | 2016 |

| Anthony Faison | 21 | Black | Male | New York | Murder | 1988 | 2001 |

| Anthony Graves | 26 | Black | Male | Texas | Murder | 1994 | 2010 |

| Anthony Johnson | 27 | Black | Male | Louisiana | Murder | 1986 | 2010 |

| Anthony Keko | 62 | Caucasian | Male | Louisiana | Murder | 1993 | 1998 |

| Anthony Lemons | 19 | Black | Male | Ohio | Murder | 1995 | 2014 |

| Anthony Ortiz | 20 | Hispanic | Male | New York | Murder | 1993 | 2011 |

| Anthony Porter | 27 | Black | Male | Illinois | Murder | 1983 | 1999 |

| Anthony Prineas | 21 | Caucasian | Male | Wisconsin | Sexual Assault | 2004 | 2012 |

| Anthony Ross | 21 | Black | Male | Illinois | Murder | 2004 | 2015 |

| Anthony Ways | 19 | Black | Male | New Jersey | Murder | 1991 | 2005 |

| Anthony Wright | 20 | Black | Male | Pennsylvania | Murder | 1993 | 2016 |

| Anthony Yarbough | 18 | Black | Male | New York | Murder | 1994 | 2014 |

| Antoine Goff | 19 | Black | Male | California | Murder | 1990 | 2003 |

| Antoine Pettiford | 23 | Black | Male | Maryland | Murder | 1995 | 2000 |

| Antoine Terry | 17 | Black | Male | Missouri | Child Sex Abuse | 2008 | 2010 |

| Antonino Lyons | 40 | Black | Male | Fed-FL | Robbery | 2001 | 2004 |

| Antonio Williams | 35 | Black | Male | Alabama | Child Sex Abuse | 2007 | 2011 |

| Antron McCray | 14 | Black | Male | New York | Sexual Assault | 1990 | 2002 |

| Antrone Johnson | 17 | Black | Male | Texas | Child Sex Abuse | 1996 | 2009 |

| Armand Villasana | 44 | Hispanic | Male | Missouri | Sexual Assault | 1999 | 2000 |

| Armando Serrano | 20 | Hispanic | Male | Illinois | Murder | 1994 | 2016 |

| Arthur Grajeda | 19 | Hispanic | Male | California | Murder | 1987 | 1991 |

| Arthur Morris | 34 | Caucasian | Male | Kansas | Assault | 2014 | 2014 |

| Arthur Mumphrey | 21 | Black | Male | Texas | Child Sex Abuse | 1986 | 2006 |

| Artis Clemmons | 29 | Black | Male | Fed-LA | Drug Possession or Sale | 1994 | 1995 |

| Arturo Cortez | 34 | Hispanic | Male | California | Drug Possession or Sale | 1998 | 2003 |

| Aubrey Ellen Shomo | 16 | Caucasian | Male | Colorado | Assault | 2001 | 2016 |

| Barry Byars | 24 | Caucasian | Male | Texas | Child Abuse | 2004 | 2005 |

| Barry Gibbs | 38 | Caucasian | Male | New York | Murder | 1988 | 2005 |

| Barshiri Sandy | 32 | Black | Male | North Carolina | Robbery | 2014 | 2016 |

| Ben Baker | 32 | Black | Male | Illinois | Drug Possession or Sale | 2006 | 2016 |

| Ben Gersten | 48 | Caucasian | Male | New York | Child Sex Abuse | 1999 | 2006 |

| Ben Kiper | 26 | Caucasian | Male | Kentucky | Child Sex Abuse | 2000 | 2007 |

| Beniah Alton Dandridge | 29 | Caucasian | Male | Alabama | Murder | 1996 | 2015 |

| Benjamin Chavis, Jr. | 23 | Black | Male | North Carolina | Assault | 1972 | 2012 |

| Benjamin Seeland | 32 | Caucasian | Male | Alaska | Assault | 2014 | 2015 |

| Bennie Starks | 26 | Black | Male | Illinois | Sexual Assault | 1986 | 2013 |

| Benny Powell | 26 | Black | Male | California | Murder | 1975 | 1992 |

| Bernard Baran | 18 | Caucasian | Male | Massachusetts | Child Sex Abuse | 1985 | 2009 |

| Bernard Ellis | 26 | Black | Male | Illinois | Murder | 1996 | 2001 |

| Bernard Webster | 18 | Black | Male | Maryland | Sexual Assault | 1983 | 2002 |

| Beth LaBatte | 24 | Caucasian | Female | Wisconsin | Murder | 1997 | 2006 |

| Betty Tyson | 24 | Black | Female | New York | Murder | 1973 | 1998 |

| Beverly Monroe | 54 | Caucasian | Female | Virginia | Murder | 1992 | 2003 |

| Billy Julian | 20 | Caucasian | Male | Indiana | Arson | 2003 | 2010 |

| Billy Wardell | 21 | Black | Male | Illinois | Sexual Assault | 1988 | 1997 |

| Bobby Johnson | 16 | Black | Male | Connecticut | Murder | 2007 | 2015 |

| Bobby Paiste Herrera | 17 | Hispanic | Male | California | Assault | 1998 | 2000 |

| Bobby Ray Dixon | 22 | Black | Male | Mississippi | Murder | 1980 | 2010 |

| Bobby Townsend | 43 | Black | Male | Mississippi | Sexual Assault | 1999 | 2001 |

| Boping Chen | 49 | Asian | Male | California | Child Sex Abuse | 2006 | 2009 |

| Brad Carter | 38 | Caucasian | Male | Illinois | Child Sex Abuse | 2013 | 2015 |

| Braden Wenger | 30 | Caucasian | Male | California | Other | 2015 | 2016 |

| Bradley Crawford | 47 | Caucasian | Male | Oklahoma | Stalking | 2003 | 2004 |

| Brandon Lewis | 23 | Caucasian | Male | Arizona | Assault | 2013 | 2014 |

| Brandy Briggs | 19 | Caucasian | Female | Texas | Child Abuse | 2000 | 2006 |

| Brenda Kniffen | 29 | Caucasian | Female | California | Child Sex Abuse | 1984 | 1996 |

| Brendan Loftus | 23 | Caucasian | Male | California | Child Sex Abuse | 1997 | 2000 |

| Brian Banks | 16 | Black | Male | California | Sexual Assault | 2003 | 2012 |

| Brian Franklin | 34 | Caucasian | Male | Texas | Child Sex Abuse | 1995 | 2016 |

| Brian McCray | 24 | Black | Male | Virginia | Murder | 1993 | 1994 |

| Bruce Godschalk | 25 | Caucasian | Male | Pennsylvania | Sexual Assault | 1987 | 2002 |

| Bruce Lisker | 17 | Caucasian | Male | California | Murder | 1985 | 2009 |

| Bruce McLaughlin | 45 | Caucasian | Male | Virginia | Child Sex Abuse | 1998 | 2002 |

| Bruce Nelson | 24 | Black | Male | Pennsylvania | Murder | 1982 | 1991 |

| Burrell Ellis | 54 | Black | Male | Georgia | Perjury | 2015 | 2017 |

| Byron Halsey | 24 | Black | Male | New Jersey | Murder | 1988 | 2007 |

| Calvin Day | 59 | Caucasian | Male | Texas | Sexual Assault | 2013 | 2015 |

| Calvin E. Washington | 30 | Black | Male | Texas | Murder | 1987 | 2001 |

| Calvin Newburn | 26 | Black | Male | California | Drug Possession or Sale | 1997 | 1999 |

| Calvin Ollins | 14 | Black | Male | Illinois | Murder | 1988 | 2001 |

| Camaran Quiambao-Holland | 19 | Hispanic | Male | Illinois | Drug Possession or Sale | 2009 | 2013 |

| Caramad Conley | 18 | Black | Male | California | Murder | 1994 | 2011 |

| Carey Clark | 37 | Caucasian | Male | North Carolina | Murder | 1996 | 1998 |

| Carl Chatman | 47 | Black | Male | Illinois | Sexual Assault | 2004 | 2013 |

| Carl Dukes | 19 | Black | Male | New York | Murder | 1998 | 2016 |

| Carl Joe Kauffman, Jr. | 21 | Caucasian | Male | Pennsylvania | Robbery | 2001 | 2004 |

| Carl Montgomery | 44 | Caucasian | Male | Illinois | Burglary/Unlawful Entry | 1984 | 1989 |

| Carl Schoppe | 30 | Hispanic | Male | California | Gun Possession or Sale | 2015 | 2016 |

| Carl Veltmann | 62 | Caucasian | Male | Fed-FL | Arson | 1992 | 1996 |

| Carlos Ashe | 18 | Black | Male | Connecticut | Murder | 2000 | 2013 |

| Carlos Davis | 18 | Black | Male | New York | Gun Possession or Sale | 1991 | 2015 |

| Carlos Flores | 44 | Hispanic | Male | Texas | Assault | 2010 | 2015 |

| Carlos Lopez-Siguenza | 21 | Hispanic | Male | New Jersey | Child Sex Abuse | 2004 | 2012 |

| Carlos Montilla | 22 | Hispanic | Male | Massachusetts | Drug Possession or Sale | 1988 | 1990 |

| Carlos Morillo | 29 | Hispanic | Male | New York | Murder | 1993 | 2011 |

| Carlos Perez | 25 | Hispanic | Male | New York | Murder | 1997 | 2012 |

| Carlos Rojas | 34 | Hispanic | Male | Fed-AL | Drug Possession or Sale | 1990 | 2002 |

| Carlton Wigfall | 46 | Black | Male | New York | Drug Possession or Sale | 2011 | 2016 |

| Carol Doggett | 36 | Caucasian | Female | Washington | Child Sex Abuse | 1995 | 2000 |

| Carol Jean Wilson | 57 | Black | Female | Michigan | Forgery | 2011 | 2013 |

| Casey Ehrlick | 19 | Caucasian | Male | Montana | Sexual Assault | 2015 | 2016 |

| Cassandra Rivera | 19 | Hispanic | Female | Texas | Child Sex Abuse | 1998 | 2016 |

| Cathy Watkins | 27 | Black | Female | New York | Murder | 1997 | 2012 |

| Ceaser Menendez | 23 | Hispanic | Male | California | Manslaughter | 1996 | 2001 |

| Chad Heins | 18 | Caucasian | Male | Florida | Murder | 1996 | 2007 |

| Charles Bunge | 38 | Caucasian | Male | New York | Attempt, Violent | 2007 | 2010 |

| Charles Fain | 33 | Caucasian | Male | Idaho | Murder | 1983 | 2001 |

| Charles Johnson | 19 | Black | Male | Illinois | Murder | 1998 | 2017 |

| Charles Maestas | 39 | Caucasian | Male | New Mexico | Sexual Assault | 2003 | 2007 |

| Charles McClaugherty | 18 | Caucasian | Male | New Mexico | Murder | 2001 | 2008 |

| Charles Palmer | 43 | Black | Male | Illinois | Murder | 2000 | 2016 |

| Charles Shepherd | 24 | Black | Male | New York | Murder | 1988 | 2001 |

| Charles Smith | 29 | Black | Male | Indiana | Murder | 1983 | 1991 |

| Charles Tomlin | 26 | Black | Male | California | Murder | 1979 | 1994 |

| Charles Wilhite | 25 | Black | Male | Massachusetts | Murder | 2010 | 2013 |

| Charlie Mitchell | 34 | Black | Male | Michigan | Murder | 1989 | 2006 |

| Chaunte Ott | 21 | Black | Male | Wisconsin | Murder | 1996 | 2009 |

| Cherice Thomas | 18 | Black | Female | California | Murder | 2009 | 2012 |

| Cheryl Adams | 26 | Caucasian | Female | Massachusetts | Theft | 1989 | 1993 |

| Cheryl Beridon | 23 | Black | Female | Louisiana | Drug Possession or Sale | 1979 | 2003 |

| Cheydrick Britt | 29 | Black | Male | Florida | Child Sex Abuse | 2004 | 2013 |

| Christopher Abernathy | 17 | Caucasian | Male | Illinois | Murder | 1987 | 2015 |

| Christopher Boots | 19 | Caucasian | Male | Oregon | Murder | 1987 | 1995 |

| Christopher Burrowes | 21 | Black | Male | Wisconsin | Child Sex Abuse | 2007 | 2009 |

| Christopher C. Smith | 32 | Caucasian | Male | Indiana | Murder | 1991 | 1993 |

| Christopher Clugston | 20 | Caucasian | Male | Florida | Murder | 1983 | 2001 |

| Christopher Cole | 19 | Caucasian | Male | Florida | Manslaughter | 1997 | 2001 |

| Christopher Coleman | 20 | Black | Male | Illinois | Sexual Assault | 1995 | 2014 |

| Christopher E. Prince | 18 | Black | Male | Virginia | Burglary/Unlawful Entry | 1994 | 1995 |

| Christopher Harding | 36 | Black | Male | Massachusetts | Assault | 1990 | 1998 |

| Christopher Long | 23 | Black | Male | Michigan | Assault | 2008 | 2008 |

| Christopher McCrimmon | 20 | Black | Male | Arizona | Murder | 1993 | 1997 |

| Christopher McDermott | 23 | Caucasian | Male | Maryland | Child Sex Abuse | 1999 | 2000 |

| Christopher Parish | 21 | Black | Male | Indiana | Attempted Murder | 1998 | 2006 |

| Christopher Roesser | 25 | Caucasian | Male | Georgia | Murder | 2008 | 2013 |

| Christopher Veltmann | 35 | Caucasian | Male | Fed-FL | Arson | 1992 | 1996 |

| Chuong Nguyen | 42 | Asian | Male | California | Other | 2013 | 2016 |

| Clarence Brandley | 29 | Black | Male | Texas | Murder | 1981 | 1990 |

| Clarence Chance | 23 | Black | Male | California | Murder | 1975 | 1992 |

| Clarissa Glenn | 34 | Black | Female | Illinois | Drug Possession or Sale | 2006 | 2016 |

| Claudia Salcedo | 21 | Hispanic | Female | Illinois | Assault | 2005 | 2007 |

| Cleveland Wright | 20 | Black | Male | District of Columbia | Murder | 1979 | 2014 |

| Clinton Potts | 30 | Caucasian | Male | Oklahoma | Murder | 2009 | 2012 |

| Clinton Turner | 31 | Black | Male | New York | Robbery | 1988 | 2005 |

| Clyde Ray Spencer | 37 | Caucasian | Male | Washington | Child Sex Abuse | 1985 | 2010 |

| Codell Griffin | 41 | Black | Male | Fed-IL | Drug Possession or Sale | 1991 | 1994 |

| Cody Marble | 17 | Caucasian | Male | Montana | Other | 2002 | 2017 |

| Colin Smith | 42 | Caucasian | Male | California | Assault | 2014 | 2016 |

| Colin Warner | 18 | Black | Male | New York | Murder | 1982 | 2001 |

| Colleen Dill Forsythe | 26 | Caucasian | Female | California | Child Sex Abuse | 1985 | 1991 |

| Connie Cunningham | 43 | Caucasian | Female | Washington | Child Sex Abuse | 1994 | 1997 |

| Connie Tindall | 21 | Black | Male | North Carolina | Assault | 1972 | 2012 |

| Cory Credell | 27 | Black | Male | South Carolina | Murder | 2001 | 2012 |

| Craig Johnson | 27 | Black | Male | Louisiana | Robbery | 1996 | 1997 |

| Crystal Weimer | 23 | Caucasian | Female | Pennsylvania | Murder | 2006 | 2016 |

| Curtis Knight | 35 | Black | Male | New Jersey | Murder | 1990 | 2001 |

| Curtis Kyles | 24 | Black | Male | Louisiana | Murder | 1984 | 1998 |

| Curtis McCarty | 20 | Caucasian | Male | Oklahoma | Murder | 1986 | 2007 |

| Curtis McGhee | 17 | Black | Male | Iowa | Murder | 1978 | 2011 |

| Curtis White | 31 | Black | Male | Virginia | Murder | 1993 | 1994 |

| Cy Greene | 19 | Black | Male | New York | Murder | 1985 | 2006 |

| Dahn Clary, Jr. | 41 | Caucasian | Male | Texas | Child Sex Abuse | 1998 | 2016 |

| Dail Stewart | 22 | Caucasian | Male | Utah | Murder | 1984 | 1992 |

| Dale Beckett | 33 | Black | Male | Ohio | Murder | 1997 | 2003 |

| Dale Duke | 42 | Caucasian | Male | Texas | Child Sex Abuse | 1992 | 2011 |

| Dale Helmig | 37 | Caucasian | Male | Missouri | Murder | 1996 | 2011 |

| Dale Palmer, Sr. | 37 | Black | Male | Ohio | Child Sex Abuse | 1994 | 1997 |

| Damaso Vega | 37 | Hispanic | Male | New Jersey | Murder | 1982 | 1989 |

| Damian Mills | 20 | Black | Male | North Carolina | Murder | 2001 | 2015 |

| Damon Corner | 23 | Black | Male | Florida | Murder | 2002 | 2012 |

| Dan Lackey | 28 | Caucasian | Male | New York | Sexual Assault | 2004 | 2007 |

| Dan Young | 30 | Black | Male | Illinois | Murder | 1994 | 2005 |

| Dana Holland | 25 | Black | Male | Illinois | Sexual Assault | 1997 | 2003 |

| Dana Payne | 28 | Caucasian | Male | Minnesota | Other Violent Felony | 1989 | 1991 |

| Dana Scheer | 34 | Caucasian | Male | Fed-FL | Fraud | 1995 | 1999 |

| Danial Williams | 25 | Caucasian | Male | Virginia | Murder | 1999 | 2016 |

| Daniel Andersen | 19 | Caucasian | Male | Illinois | Murder | 1982 | 2015 |

| Daniel Bolstad | 37 | Caucasian | Male | Wisconsin | Sexual Assault | 2007 | 2015 |

| Daniel Crosby | 31 | Caucasian | Male | Montana | Child Sex Abuse | 1996 | 2008 |

| Daniel Cvijanovich | 26 | Caucasian | Male | Fed-ND | Other Nonviolent Felony | 2007 | 2011 |

| Daniel Gonzalez | 18 | Hispanic | Male | California | Assault | 2006 | 2007 |

| Daniel Larsen | 30 | Caucasian | Male | California | Other Nonviolent Felony | 1999 | 2014 |

| Daniel Pickett | 43 | Caucasian | Male | California | Child Sex Abuse | 2004 | 2004 |

| Daniel Purtell | 21 | Caucasian | Male | Pennsylvania | Sexual Assault | 2002 | 2004 |

| Daniel Roy Settle | 18 | Caucasian | Male | Texas | Drug Possession or Sale | 1999 | 2011 |

| Daniel Taylor | 17 | Black | Male | Illinois | Murder | 1995 | 2013 |

| Daniel Terens | 27 | Caucasian | Male | Wisconsin | Manslaughter | 1991 | 1993 |

| Danielle Enriquez | 28 | Hispanic | Female | Illinois | Drug Possession or Sale | 2011 | 2013 |

| Danny Colon | 26 | Hispanic | Male | New York | Murder | 1993 | 2011 |

| Danny Davis | 25 | Black | Male | Fed-LA | Drug Possession or Sale | 2006 | 2006 |

| Danny Sarita | 25 | Hispanic | Male | New York | Assault | 2009 | 2012 |

| Darcus Henry | 21 | Black | Male | Connecticut | Murder | 1999 | 2013 |

| Darlene Span | 39 | Caucasian | Female | Fed-AZ | Assault | 1990 | 1996 |

| Darrell Houston | 23 | Black | Male | Ohio | Murder | 1992 | 2010 |

| Darren Felix | 19 | Black | Male | New York | Attempted Murder | 2004 | 2010 |

| Darrian Mark Lawrence | 20 | Black | Male | Florida | Murder | 2000 | 2005 |

| Darryl Adams | 25 | Black | Male | Texas | Sexual Assault | 1992 | 2017 |

| Darryl Austin | 22 | Black | Male | New York | Murder | 1988 | 2014 |

| Darryl Burton | 22 | Black | Male | Missouri | Murder | 1985 | 2008 |

| Darryl Howard | 29 | Black | Male | North Carolina | Murder | 1995 | 2016 |

| Darryl Hunt | 19 | Black | Male | North Carolina | Murder | 1985 | 2004 |

| Darryl Pinkins | 37 | Black | Male | Indiana | Sexual Assault | 1991 | 2016 |

| David A. Gray | 25 | Black | Male | Illinois | Attempted Murder | 1978 | 1999 |

| David Ayers | 42 | Black | Male | Ohio | Murder | 2000 | 2011 |

| David Bates | 18 | Black | Male | Illinois | Murder | 1985 | 2015 |

| David Boyce | 19 | Caucasian | Male | Virginia | Murder | 1991 | 2013 |

| David Bryson | 28 | Caucasian | Male | Oklahoma | Sexual Assault | 1983 | 2003 |

| David Camm | 36 | Caucasian | Male | Indiana | Murder | 2002 | 2013 |

| David DeSimone | 45 | Caucasian | Male | Iowa | Sexual Assault | 2005 | 2012 |

| David Dutcher | 45 | Caucasian | Male | California | Traffic Offense | 2009 | 2012 |

| David Fauntleroy | 22 | Black | Male | Illinois | Murder | 1986 | 2009 |

| David Garner | 34 | Black | Male | Fed-OH | Robbery | 2005 | 2008 |

| David Ghysels, Jr. | 45 | Caucasian | Male | Fed-NY | Fraud | 2009 | 2014 |

| David Gladden | 36 | Black | Male | Pennsylvania | Murder | 1995 | 2007 |

| David Gonzalez | 33 | Hispanic | Male | South Dakota | Child Sex Abuse | 1999 | 2001 |

| David Grannis | 21 | Caucasian | Male | Arizona | Murder | 1991 | 1996 |

| David Housler, Jr. | 19 | Caucasian | Male | Tennessee | Murder | 1997 | 2014 |

| David Kunze | 44 | Caucasian | Male | Washington | Murder | 1997 | 2001 |

| David Lazzell | 32 | Caucasian | Male | Louisiana | Child Sex Abuse | 1991 | 2007 |

| David McCallum | 16 | Black | Male | New York | Murder | 1986 | 2014 |

| David McMahan | 40 | Caucasian | Male | Maine | Assault | 2000 | 2001 |

| David Moreno | 19 | Hispanic | Male | California | Murder | 1998 | 2000 |

| David Munchinski | 25 | Caucasian | Male | Pennsylvania | Murder | 1986 | 2013 |

| David Parse | 42 | Caucasian | Male | Fed-NY | Tax Evasion/Fraud | 2011 | 2016 |

| David Peralta | 23 | Hispanic | Male | Georgia | Murder | 2001 | 2013 |

| David Ranta | 35 | Caucasian | Male | New York | Murder | 1991 | 2013 |

| David Schaaf | 40 | Caucasian | Male | Pennsylvania | Attempted Murder | 2003 | 2006 |

| David Sipe | 27 | Caucasian | Male | Fed-TX | Assault | 2001 | 2007 |

| David Wong | 23 | Asian | Male | New York | Murder | 1987 | 2004 |

| Davie Hurt | 17 | Black | Male | West Virginia | Murder | 1998 | 2014 |

| Davonn Robinson | 17 | Black | Male | Wisconsin | Child Sex Abuse | 2006 | 2010 |

| Davontae Sanford | 14 | Black | Male | Michigan | Murder | 2008 | 2016 |

| De'Marchoe Carpenter | 17 | Black | Male | Oklahoma | Murder | 1995 | 2016 |

| Deborah McCuan | 25 | Caucasian | Female | California | Child Sex Abuse | 1984 | 1996 |

| Debra Green | 31 | Black | Female | Illinois | Assault | 2010 | 2011 |

| Debra Milke | 25 | Caucasian | Female | Arizona | Murder | 1990 | 2015 |

| Debra Shelden | 26 | Caucasian | Female | Nebraska | Murder | 1989 | 2009 |

| Declan Woods | 43 | Caucasian | Male | California | Traffic Offense | 2007 | 2012 |

| Demetrius Smith | 25 | Black | Male | Maryland | Murder | 2010 | 2012 |

| Denis Field | 46 | Caucasian | Male | Fed-NY | Tax Evasion/Fraud | 2011 | 2013 |

| Dennis Cerrano | 46 | Caucasian | Male | California | Child Sex Abuse | 1998 | 2000 |

| Dennis Devlin | 38 | Caucasian | Male | Florida | Child Sex Abuse | 1995 | 2002 |

| Dennis Fritz | 22 | Caucasian | Male | Oklahoma | Murder | 1988 | 1999 |

| Dennis Halstead | 26 | Caucasian | Male | New York | Murder | 1986 | 2005 |

| Dennis Lewchuk | 33 | Caucasian | Male | Nebraska | Assault | 1980 | 1996 |

| Dennis Tomasik | 34 | Caucasian | Male | Michigan | Child Sex Abuse | 2007 | 2017 |

| Dennis Williams | 21 | Black | Male | Illinois | Murder | 1978 | 1996 |

| Deon Patrick | 20 | Black | Male | Illinois | Murder | 1995 | 2014 |

| Derek Tice | 27 | Caucasian | Male | Virginia | Murder | 2000 | 2011 |

| Derrick Deacon | 34 | Black | Male | New York | Murder | 1989 | 2013 |

| Derrick Hamilton | 25 | Black | Male | New York | Murder | 1992 | 2015 |

| Derrick Jamison | 23 | Black | Male | Ohio | Murder | 1985 | 2005 |

| Derrick Robinson | 30 | Black | Male | Florida | Murder | 1989 | 1991 |

| DeShawn Reed | 24 | Black | Male | Michigan | Attempted Murder | 2001 | 2009 |

| Devon Ayers | 18 | Black | Male | New York | Murder | 1997 | 2012 |

| Devron Hodges | 21 | Black | Male | Texas | Robbery | 2013 | 2015 |

| Dewey Bozella | 16 | Black | Male | New York | Murder | 1983 | 2009 |

| Dewey Davis | 53 | Caucasian | Male | West Virginia | Sexual Assault | 1987 | 1995 |

| Dewey Jones | 30 | Caucasian | Male | Ohio | Murder | 1995 | 2014 |

| Dhoruba bin Wahad | 26 | Black | Male | New York | Attempted Murder | 1973 | 1995 |

| Domingo Calderon, III | 26 | Hispanic | Male | Texas | Child Sex Abuse | 2005 | 2010 |

| Dominic Okongwu | 41 | Black | Male | New York | Child Sex Abuse | 1993 | 2011 |

| Dominique Brim | 14 | Black | Female | Michigan | Assault | 2002 | 2002 |

| Don Ray Adams | 32 | Black | Male | Pennsylvania | Murder | 1992 | 2011 |

| Don Taylor | 20 | Black | Male | New York | Murder | 1989 | 2004 |

| Donald Barnes, Jr. | 32 | Caucasian | Male | Florida | Child Sex Abuse | 2011 | 2014 |

| Donald Brock | Black | Male | Illinois | Theft | 1989 | 1989 | |

| Donald Clark | 35 | Caucasian | Male | Iowa | Child Sex Abuse | 2010 | 2016 |

| Donald Dixon | 18 | Black | Male | Missouri | Murder | 1985 | 2001 |

| Donald Eugene Gates | 30 | Black | Male | District of Columbia | Murder | 1982 | 2009 |

| Donald Gainer | 31 | Caucasian | Male | Pennsylvania | Arson | 1985 | 1992 |

| Donald Glassman | 36 | Caucasian | Male | New York | Sexual Assault | 2007 | 2009 |

| Donald Hannon | 18 | Caucasian | Male | Iowa | Sexual Assault | 1990 | 1992 |

| Donald Heistand | 29 | Caucasian | Male | Michigan | Accessory to Murder | 1989 | 2002 |

| Donald Kelly | 26 | Caucasian | Male | Pennsylvania | Murder | 1990 | 1993 |

| Donald Letcher | 29 | Caucasian | Male | South Dakota | Child Sex Abuse | 1995 | 1996 |

| Donald Paradis | 30 | Caucasian | Male | Idaho | Murder | 1981 | 2001 |

| Donald Reynolds | 20 | Black | Male | Illinois | Sexual Assault | 1988 | 1997 |

| Donna Sue Hubbard | 30 | Caucasian | Female | California | Child Sex Abuse | 1985 | 1995 |

| Donnell Johnson | 16 | Black | Male | Massachusetts | Murder | 1996 | 2000 |

| Donnell Thomas | 22 | Black | Male | New York | Child Sex Abuse | 2007 | 2011 |

| Donovan Allen | 18 | Caucasian | Male | Washington | Murder | 2002 | 2015 |

| Donya Davis | 28 | Black | Male | Michigan | Sexual Assault | 2007 | 2014 |

| Doris Green | 34 | Caucasian | Female | Washington | Child Sex Abuse | 1995 | 1999 |

| Drew Whitley | 32 | Black | Male | Pennsylvania | Murder | 1989 | 2006 |

| Dwayne Provience | 27 | Black | Male | Michigan | Murder | 2001 | 2010 |

| Dwight Allen | 28 | Black | Male | Maryland | Assault | 2000 | 2003 |

| Dwight Grandson | 17 | Black | Male | District of Columbia | Murder | 2006 | 2011 |

| Dwight LaBran | 23 | Black | Male | Louisiana | Murder | 1997 | 2001 |

| Dwight Love | 22 | Black | Male | Michigan | Murder | 1982 | 2001 |

| E. Robert Wallach | 50 | Caucasian | Male | Fed-NY | Fraud | 1989 | 1993 |

| Earl Berryman | 24 | Black | Male | New Jersey | Sexual Assault | 1985 | 1997 |

| Earl Truvia | 17 | Black | Male | Louisiana | Murder | 1976 | 2003 |

| Earl Washington | 22 | Black | Male | Virginia | Murder | 1984 | 2000 |

| Earnest Leap | 31 | Caucasian | Male | Missouri | Child Sex Abuse | 1992 | 2016 |

| Edar Duarte Santos | 26 | Hispanic | Male | Illinois | Murder | 2002 | 2003 |

| Eddie Andre | 41 | Black | Male | New York | Murder | 1988 | 1994 |

| Eddie Lowery | 22 | Caucasian | Male | Kansas | Sexual Assault | 1982 | 2003 |

| Eddie Triplett | 38 | Black | Male | Louisiana | Drug Possession or Sale | 1998 | 2011 |

| Edgar Coker | 15 | Black | Male | Virginia | Sexual Assault | 2007 | 2014 |

| Edgar Rivas | 37 | Hispanic | Male | Fed-NY | Drug Possession or Sale | 2003 | 2004 |

| Edward Baker | 17 | Black | Male | Pennsylvania | Murder | 1974 | 2002 |

| Edward Colomb | 26 | Black | Male | Fed-LA | Drug Possession or Sale | 2006 | 2006 |

| Edward Honaker | 33 | Caucasian | Male | Virginia | Sexual Assault | 1985 | 1994 |

| Edward McInnis | 27 | Black | Male | North Carolina | Sexual Assault | 1988 | 2015 |

| Edward McNenney | 40 | Caucasian | Male | New York | Fraud | 2008 | 2011 |

| Edward Stewart | 26 | Black | Male | Pennsylvania | Murder | 2007 | 2015 |

| Edward Williams | 25 | Black | Male | Ohio | Assault | 1997 | 2015 |

| Edwin Rodriguez | 18 | Hispanic | Male | New Jersey | Other | 2014 | 2014 |

| Edwin Wilson | 49 | Caucasian | Male | Fed-VA | Gun Possession or Sale | 1983 | 2004 |

| Elizabeth Ramirez | 20 | Hispanic | Female | Texas | Child Sex Abuse | 1998 | 2016 |

| Ellen Reasonover | 24 | Black | Female | Missouri | Murder | 1983 | 1999 |

| Elmer Pratt | 21 | Black | Male | California | Murder | 1972 | 1999 |

| Elroy Lucky Jones | 26 | Black | Male | Michigan | Murder | 2006 | 2014 |

| Emmaline Williams | 43 | Black | Female | Illinois | Child Sex Abuse | 1986 | 1995 |

| Eric Caine | 19 | Black | Male | Illinois | Murder | 1989 | 2011 |

| Eric Glisson | 18 | Black | Male | New York | Murder | 1997 | 2012 |

| Eric Jackson-Knight | 21 | Black | Male | New York | Murder | 1980 | 1994 |

| Eric Lynn | 25 | Black | Male | Maryland | Murder | 1994 | 2007 |

| Eric Proctor | 18 | Caucasian | Male | Oregon | Murder | 1986 | 1995 |

| Eric Robinson | 23 | Black | Male | California | Murder | 1994 | 2007 |

| Eric Sarsfield | 23 | Caucasian | Male | Massachusetts | Sexual Assault | 1987 | 2000 |

| Ernest Matthews | 20 | Black | Male | North Carolina | Murder | 1993 | 2016 |

| Eugene Vent | 17 | Native American | Male | Alaska | Murder | 1999 | 2015 |

| Evan Lee Deakle, Jr. | 59 | Caucasian | Male | Alabama | Child Sex Abuse | 2015 | 2015 |

| Everton Wagstaffe | 23 | Black | Male | New York | Kidnapping | 1993 | 2015 |

| Ezequiel Apolo-Albino | 55 | Hispanic | Male | Washington | Child Sex Abuse | 2009 | 2016 |

| Federico Macias | 31 | Hispanic | Male | Texas | Murder | 1984 | 1993 |

| Fernando Bermudez | 21 | Hispanic | Male | New York | Murder | 1992 | 2009 |

| Floyd Bledsoe | 23 | Caucasian | Male | Kansas | Murder | 2000 | 2015 |

| Frances Ballard | 54 | Caucasian | Female | Tennessee | Child Sex Abuse | 1987 | 1993 |

| Francisco Hernandez | 26 | Hispanic | Male | California | Murder | 2002 | 2005 |

| Francisco Islas, Jr. | 47 | Hispanic | Male | Arizona | Drug Possession or Sale | 2013 | 2013 |

| Frank Lee Smith | 37 | Black | Male | Florida | Murder | 1986 | 2000 |

| Frank Lind | 44 | Caucasian | Male | California | Child Sex Abuse | 2002 | 2005 |

| Frank O'Connell | 25 | Caucasian | Male | California | Murder | 1985 | 2012 |

| Frank Sealie | 23 | Black | Male | Alabama | Murder | 2014 | 2015 |

| Franklin Beauchamp | 27 | Hispanic | Male | New York | Child Sex Abuse | 1986 | 1989 |

| Franky Carrillo | 15 | Hispanic | Male | California | Murder | 1992 | 2011 |

| Fredda Susie Mowbray | 39 | Caucasian | Female | Texas | Murder | 1988 | 1998 |

| Freddie Peacock | 26 | Black | Male | New York | Sexual Assault | 1976 | 2010 |

| Gary Dotson | 20 | Caucasian | Male | Illinois | Sexual Assault | 1979 | 1989 |

| Gary Engel | 33 | Caucasian | Male | Missouri | Kidnapping | 1991 | 2010 |

| Gary Gathers | 17 | Black | Male | District of Columbia | Murder | 1994 | 2015 |

| Gary Gauger | 41 | Caucasian | Male | Illinois | Murder | 1993 | 1996 |

| Gary Lamar James | 23 | Black | Male | Ohio | Murder | 1977 | 2003 |

| Gary Nelson | 29 | Black | Male | Georgia | Murder | 1980 | 1991 |

| Gary Woodside, Jr. | 20 | Caucasian | Male | New York | Manslaughter | 1989 | 2007 |

| Gayle Dove | 41 | Caucasian | Female | Texas | Child Sex Abuse | 1986 | 1989 |

| Gene Bibbins | 29 | Black | Male | Louisiana | Child Sex Abuse | 1987 | 2003 |

| Gene Curtis Ballinger | 45 | Caucasian | Male | New Mexico | Murder | 1981 | 1993 |

| Gene Graham | 40 | Caucasian | Male | Oklahoma | Child Sex Abuse | 2013 | 2016 |

| George Allen, Jr. | 25 | Black | Male | Missouri | Murder | 1983 | 2013 |

| George Franklin | 30 | Caucasian | Male | California | Murder | 1990 | 1996 |

| George Frese | 20 | Native American | Male | Alaska | Murder | 1999 | 2015 |

| George Gross | 38 | Caucasian | Male | New Jersey | Child Sex Abuse | 1998 | 2001 |

| George Lindstadt | 42 | Caucasian | Male | New York | Child Sex Abuse | 1989 | 2001 |

| George Seiber | 41 | Caucasian | Male | Ohio | Assault | 1987 | 1999 |

| George Walls | 39 | Black | Male | Pennsylvania | Sexual Assault | 2003 | 2011 |

| Gerald Atlas | 25 | Black | Male | California | Attempted Murder | 1990 | 1998 |

| Gerald Burge | 29 | Caucasian | Male | Louisiana | Murder | 1986 | 1992 |

| Gerald Davis | 26 | Caucasian | Male | West Virginia | Sexual Assault | 1986 | 1995 |

| Gerald Minsky | 42 | Caucasian | Male | Fed-KY | Conspiracy | 1991 | 1992 |

| Gilbert Alejandro | 35 | Hispanic | Male | Texas | Sexual Assault | 1990 | 1994 |

| Gina Miller | 25 | Caucasian | Female | California | Child Sex Abuse | 1985 | 1991 |

| Glen Edward Chapman | 24 | Black | Male | North Carolina | Murder | 1994 | 2008 |

| Glen Nickerson | 29 | Caucasian | Male | California | Murder | 1987 | 2003 |

| Glen Woodall | 28 | Caucasian | Male | West Virginia | Sexual Assault | 1987 | 1992 |

| Glenn Davis, Jr. | 18 | Black | Male | Louisiana | Murder | 1993 | 2010 |

| Glenn Ford | 34 | Black | Male | Louisiana | Murder | 1984 | 2014 |

| Gloria Killian | 35 | Caucasian | Female | California | Murder | 1986 | 2002 |

| Gloria Salcedo | 46 | Hispanic | Female | Illinois | Assault | 2005 | 2007 |

| Gordon Steidl | 35 | Caucasian | Male | Illinois | Murder | 1987 | 2004 |

| Grace Dill | 50 | Caucasian | Female | California | Child Sex Abuse | 1985 | 1991 |

| Grant Self | 31 | Caucasian | Male | California | Child Sex Abuse | 1985 | 2008 |

| Gregory Bright | 20 | Black | Male | Louisiana | Murder | 1976 | 2003 |

| Gregory Taylor | 28 | Caucasian | Male | North Carolina | Murder | 1993 | 2010 |

| Gregory Wallis | 27 | Caucasian | Male | Texas | Sexual Assault | 1989 | 2007 |

| Gyronne Buckley | 44 | Black | Male | Arkansas | Drug Possession or Sale | 1999 | 2010 |

| Harold Everett | 65 | Caucasian | Male | Washington | Child Sex Abuse | 1994 | 1998 |

| Harold Grant Snowden | 38 | Caucasian | Male | Florida | Child Sex Abuse | 1986 | 1998 |

| Harold Hall | 37 | Black | Male | California | Murder | 1990 | 2004 |

| Harold Hill | 16 | Black | Male | Illinois | Murder | 1994 | 2005 |

| Harold Richardson | 16 | Black | Male | Illinois | Murder | 1997 | 2012 |

| Harold Sullivan | 31 | Caucasian | Male | Massachusetts | Murder | 1986 | 1990 |

| Harold Wright, Jr. | 32 | Black | Male | Washington | Sexual Assault | 2007 | 2013 |

| Hayes Williams | 19 | Black | Male | Louisiana | Murder | 1968 | 1997 |

| Henry Cunningham | 46 | Caucasian | Male | Washington | Child Sex Abuse | 1994 | 1999 |

| Henry McCollum | 19 | Black | Male | North Carolina | Murder | 1984 | 2014 |

| Henry Surpris | 34 | Black | Male | North Carolina | Robbery | 2014 | 2016 |

| Henry Tameleo | 63 | Caucasian | Male | Massachusetts | Murder | 1968 | 2001 |

| Herbert Whitlock | 39 | Caucasian | Male | Illinois | Murder | 1987 | 2008 |

| Hilliard Fields | 25 | Black | Male | Texas | Child Sex Abuse | 1997 | 2011 |

| Howard Dudley | 34 | Black | Male | North Carolina | Child Sex Abuse | 1992 | 2016 |

| Howard Weimer | 57 | Caucasian | Male | California | Child Sex Abuse | 1985 | 2005 |

| Idella Everett | 41 | Caucasian | Female | Washington | Child Sex Abuse | 1994 | 1998 |

| Idris Fahra | 21 | Black | Male | Fed-TN | Other Violent Felony | 2012 | 2016 |

| Ignacio Varela | 42 | Hispanic | Male | Illinois | Murder | 1982 | 1991 |

| Ingmar Guandique | 19 | Hispanic | Male | District of Columbia | Murder | 2010 | 2016 |

| Isaac Knapper | 17 | Black | Male | Louisiana | Murder | 1979 | 1991 |

| Isaiah McCoy | 22 | Black | Male | Delaware | Murder | 2012 | 2017 |

| Isauro Sanchez | 20 | Hispanic | Male | Illinois | Murder | 1982 | 1991 |

| Jabbar Collins | 20 | Black | Male | New York | Murder | 1995 | 2010 |

| Jack Dinning | 38 | Caucasian | Male | Georgia | Murder | 1993 | 1997 |

| Jack McCullough | 18 | Caucasian | Male | Illinois | Murder | 2012 | 2016 |

| Jack Ray Broam | 29 | Caucasian | Male | Nevada | Child Sex Abuse | 1990 | 1998 |

| Jacob Beard | 34 | Caucasian | Male | West Virginia | Murder | 1993 | 2000 |

| Jacob Trakhtenberg | 67 | Caucasian | Male | Michigan | Child Sex Abuse | 2006 | 2013 |

| Jacqueline Latta | 27 | Caucasian | Female | Indiana | Murder | 1990 | 2002 |

| Jacques Rivera | 23 | Hispanic | Male | Illinois | Murder | 1990 | 2011 |

| Jamar Smythe | 30 | Black | Male | New York | Drug Possession or Sale | 2013 | 2015 |

| James Albert Robison | 53 | Caucasian | Male | Arizona | Murder | 1977 | 1993 |

| James Andrews | 21 | Black | Male | Illinois | Murder | 1985 | 2008 |

| James Bell, Jr. | 27 | Black | Male | Pennsylvania | Drug Possession or Sale | 2008 | 2014 |

| James Blackshire | 18 | Black | Male | Texas | Child Sex Abuse | 1995 | 2009 |

| James Bowman | 18 | Black | Male | Missouri | Murder | 1986 | 2001 |

| James Bryant | 38 | Black | Male | California | Drug Possession or Sale | 1997 | 2000 |

| James Catton | 43 | Caucasian | Male | Fed-IL | Fraud | 1994 | 2004 |

| James Dean | 20 | Caucasian | Male | Nebraska | Murder | 1989 | 2009 |

| James E. Richardson, Jr. | 36 | Caucasian | Male | West Virginia | Murder | 1989 | 1999 |

| James Eardley | 23 | Caucasian | Male | Illinois | Conspiracy | 1990 | 1991 |

| James Edwards | 44 | Black | Male | Illinois | Murder | 1996 | 2012 |

| James Fisher | 32 | Caucasian | Male | Fed-TX | Conspiracy | 1995 | 1997 |

| James Green | 46 | Black | Male | Tennessee | Child Sex Abuse | 2006 | 2008 |

| James Grissom | 43 | Caucasian | Male | Michigan | Sexual Assault | 2003 | 2012 |

| James Haley | 24 | Black | Male | Massachusetts | Murder | 1972 | 2008 |

| James Harden | 16 | Black | Male | Illinois | Murder | 1995 | 2011 |

| James Hill | 17 | Black | Male | Indiana | Sexual Assault | 1982 | 2009 |

| James Joseph Richardson | 31 | Black | Male | Florida | Murder | 1968 | 1989 |

| James Kluppelberg | 18 | Caucasian | Male | Illinois | Murder | 1989 | 2012 |

| James L. Owens | 22 | Caucasian | Male | Maryland | Murder | 1988 | 2008 |

| James McKoy | 17 | Black | Male | North Carolina | Assault | 1972 | 2012 |

| James Newsome | 24 | Black | Male | Illinois | Murder | 1980 | 1995 |

| James Norman Perry | 31 | Caucasian | Male | Michigan | Child Sex Abuse | 2006 | 2008 |

| James S. Anderson | 26 | Black | Male | Washington | Robbery | 2005 | 2009 |

| James Shortt | 21 | Black | Male | California | Murder | 1982 | 2010 |

| James Simmons | 47 | Black | Male | Washington | Drug Possession or Sale | 2007 | 2010 |

| James Strughold | 53 | Caucasian | Male | Missouri | Child Sex Abuse | 1997 | 1999 |

| James Thomas Hart | 43 | Caucasian | Male | California | Child Sex Abuse | 1990 | 2001 |

| James Vaughan III | 28 | Black | Male | Ohio | Child Sex Abuse | 2008 | 2009 |

| James Walker | 30 | Black | Male | New York | Murder | 1971 | 1990 |

| James Williams | 50 | Caucasian | Male | Georgia | Murder | 1982 | 1989 |

| Jarrett M. Adams | 17 | Black | Male | Wisconsin | Sexual Assault | 2000 | 2007 |

| Jason Barber | 21 | Caucasian | Male | Texas | Murder | 1997 | 2000 |

| Jason Ellison | 23 | Caucasian | Male | Kansas | Sexual Assault | 2006 | 2011 |

| Jason Girts | 22 | Caucasian | Male | Kentucky | Child Sex Abuse | 2006 | 2008 |

| Jason Roberts | 16 | Caucasian | Male | South Carolina | Murder | 1995 | 2005 |

| Jason Strong | 24 | Caucasian | Male | Illinois | Murder | 2000 | 2015 |

| Javon Patterson | 25 | Black | Male | Illinois | Gun Possession or Sale | 2007 | 2010 |

| Jay C. Smith | 50 | Caucasian | Male | Pennsylvania | Murder | 1986 | 1992 |

| Jay Cee Manning | 28 | Caucasian | Male | Nevada | Child Sex Abuse | 1990 | 1998 |

| Jeanie Becerra | 21 | Caucasian | Female | Kansas | Obstruction of Justice | 2014 | 2014 |

| Jed Allen Gressman | 22 | Caucasian | Male | Utah | Sexual Assault | 1993 | 1996 |

| Jeff Schmieder | 41 | Caucasian | Male | Washington | Sexual Assault | 1998 | 1999 |

| Jeffery Funes | 15 | Hispanic | Male | California | Assault | 2006 | 2006 |

| Jeffery Willett | 29 | Caucasian | Male | Wisconsin | Child Sex Abuse | 2007 | 2010 |

| Jeffrey Blake | 21 | Black | Male | New York | Murder | 1991 | 1998 |

| Jeffrey Cox | 22 | Caucasian | Male | Virginia | Murder | 1991 | 2001 |

| Jeffrey Modahl | 29 | Caucasian | Male | California | Child Sex Abuse | 1986 | 1999 |

| Jeffrey Moldowan | 20 | Caucasian | Male | Michigan | Sexual Assault | 1991 | 2003 |

| Jeffrey Santos | 40 | Black | Male | New York | Assault | 1998 | 2004 |

| Jeffrey Todd Pierce | 23 | Caucasian | Male | Oklahoma | Sexual Assault | 1986 | 2001 |

| Jennifer Wilcox | 20 | Caucasian | Female | Ohio | Child Sex Abuse | 1985 | 1997 |

| Jepheth Barnes | 51 | Black | Male | South Carolina | Child Sex Abuse | 1996 | 2003 |

| Jeremiah Brinson | 28 | Black | Male | New York | Robbery | 1999 | 2009 |

| Jermaine Dollard | 38 | Black | Male | Delaware | Drug Possession or Sale | 2013 | 2015 |

| Jermaine Walker | 29 | Black | Male | Illinois | Drug Possession or Sale | 2006 | 2016 |

| Jerome Cruz | 24 | Hispanic | Male | New York | Drug Possession or Sale | 2007 | 2007 |

| Jerome Morgan | 17 | Black | Male | Louisiana | Murder | 1994 | 2016 |

| Jerome Thagard | 16 | Black | Male | New York | Murder | 2010 | 2014 |

| Jerry Brock | 35 | Black | Male | Washington | Child Sex Abuse | 1995 | 2014 |

| Jerry Jacobs | 18 | Black | Male | North Carolina | Assault | 1972 | 2012 |

| Jerry Jamaal Jones | 24 | Black | Male | Wisconsin | Assault | 2010 | 2011 |

| Jerry Span | 57 | Caucasian | Male | Fed-AZ | Assault | 1990 | 1996 |

| Jerry Watkins | 26 | Caucasian | Male | Indiana | Murder | 1986 | 2000 |

| Jesse Allen Cheshire | 37 | Caucasian | Male | Oklahoma | Child Sex Abuse | 2004 | 2008 |

| Jesse Alvarez | 19 | Hispanic | Male | California | Manslaughter | 1996 | 2001 |

| Jesse Miller, Jr. | 17 | Black | Male | Florida | Murder | 2009 | 2014 |

| Jesse Risha | 47 | Caucasian | Male | Fed-PA | Attempt, Violent | 2004 | 2006 |

| Jessica Elsayed | 21 | Caucasian | Female | Illinois | Drug Possession or Sale | 2012 | 2013 |

| Jesus Ramirez | 48 | Hispanic | Male | Texas | Murder | 1998 | 2008 |

| Jesus Torres | 29 | Hispanic | Male | New York | Child Sex Abuse | 1986 | 1990 |

| Jimmie Gardner | 20 | Black | Male | West Virginia | Sexual Assault | 1990 | 2016 |

| Jimmy Bass | 18 | Black | Male | Mississippi | Robbery | 1988 | 2010 |

| Jimmy Lee Baker | 22 | Caucasian | Male | Oklahoma | Assault | 2009 | 2010 |

| Jimmy Ray Bromgard | 18 | Caucasian | Male | Montana | Child Sex Abuse | 1987 | 2002 |

| Joaquin Jose Martinez | 23 | Hispanic | Male | Florida | Murder | 1997 | 2001 |

| Joe Burrows | 35 | Caucasian | Male | Illinois | Murder | 1989 | 1996 |

| Joe D'Ambrosio | 26 | Caucasian | Male | Ohio | Murder | 1989 | 2012 |

| Joe Elizondo | 49 | Hispanic | Male | Texas | Child Sex Abuse | 1984 | 1997 |

| Joe Lea | 24 | Hispanic | Male | California | Child Sex Abuse | 2000 | 2009 |

| Joe Sidney Williams | 19 | Black | Male | Texas | Murder | 1987 | 1993 |

| Joel Alcox | 22 | Caucasian | Male | California | Murder | 1987 | 2016 |

| Joel Covender | 26 | Caucasian | Male | Ohio | Child Sex Abuse | 1996 | 2014 |

| Joel Fowler | 17 | Black | Male | New York | Murder | 2009 | 2015 |

| Joel Miller | 35 | Caucasian | Male | Fed-CA | Gun Possession or Sale | 2012 | 2014 |

| John Carney | 32 | Caucasian | Male | Fed-TX | Conspiracy | 1995 | 1997 |

| John Duval | 21 | Black | Male | New York | Murder | 1973 | 2000 |

| John Edward Smith | 18 | Black | Male | California | Murder | 1994 | 2012 |

| John Fitzgerald | 40 | Caucasian | Male | Fed-CA | Tax Evasion/Fraud | 2007 | 2009 |

| John Holsomback | 33 | Caucasian | Male | Alabama | Child Sex Abuse | 1988 | 2000 |

| John Hooper | 48 | Black | Male | New York | Gun Possession or Sale | 2013 | 2015 |

| John Jackson | 59 | Black | Male | Washington | Drug Possession or Sale | 1996 | 2001 |

| John Kogut | 19 | Caucasian | Male | New York | Murder | 1986 | 2005 |

| John Manfredi | 48 | Caucasian | Male | New York | Bribery | 1989 | 1994 |

| John Michael Harvey | 24 | Caucasian | Male | Texas | Child Sex Abuse | 1992 | 2005 |

| John Mooney | 19 | Caucasian | Male | Maryland | Murder | 2010 | 2014 |

| John O'Hara | 32 | Caucasian | Male | New York | Fraud | 1997 | 2017 |

| John Palazzolo | 48 | Caucasian | Male | Michigan | Sexual Assault | 2006 | 2012 |

| John Palladino | 41 | Caucasian | Male | Connecticut | Sexual Assault | 2000 | 2002 |

| John Peel | 18 | Caucasian | Male | Florida | Manslaughter | 2000 | 2002 |

| John Randall Alexander | 22 | Caucasian | Male | Mississippi | Murder | 1989 | 2010 |

| John Restivo | 25 | Caucasian | Male | New York | Murder | 1986 | 2005 |

| John Sosnovske | 39 | Caucasian | Male | Oregon | Murder | 1991 | 1995 |

| John Stoll | 41 | Caucasian | Male | California | Child Sex Abuse | 1985 | 2004 |

| John Street | 36 | Caucasian | Male | Fed-MO | Murder | 2006 | 2009 |

| John Tennison | 17 | Black | Male | California | Murder | 1990 | 2003 |

| John Thompson | 22 | Black | Male | Louisiana | Murder | 1985 | 2003 |

| John Willis | 42 | Black | Male | Illinois | Sexual Assault | 1993 | 1999 |

| Johnathan Montgomery | 14 | Caucasian | Male | Virginia | Sexual Assault | 2008 | 2013 |

| Johnnie Johnson | 18 | Black | Male | Connecticut | Murder | 2001 | 2013 |

| Johnnie O'Neal | 25 | Black | Male | New York | Sexual Assault | 1985 | 2013 |

| Johnnie Savory | 14 | Black | Male | Illinois | Murder | 1977 | 2015 |

| Johnny Hincapie | 18 | Hispanic | Male | New York | Murder | 1991 | 2017 |

| Johnny Lee Wilson | 20 | Caucasian | Male | Missouri | Murder | 1987 | 1995 |

| Johnny Reeves | 41 | Caucasian | Male | Ohio | Child Sex Abuse | 1989 | 1999 |

| Johnny Small | 15 | Caucasian | Male | North Carolina | Murder | 1989 | 2016 |

| Johnny Vargas-Cintron | 34 | Hispanic | Male | Massachusetts | Drug Possession or Sale | 2011 | 2013 |

| Jon Keith Smith | 17 | Black | Male | Missouri | Murder | 1987 | 2000 |

| Jonathan Barr | 14 | Black | Male | Illinois | Murder | 1997 | 2011 |

| Jonathan Dominguez | 15 | Hispanic | Male | California | Assault | 2006 | 2006 |

| Jonathan Fleming | 27 | Black | Male | New York | Murder | 1990 | 2014 |

| Jonathan Leal-Del Carmen | 44 | Hispanic | Male | Fed-CA | Immigration | 2010 | 2012 |

| Jonathan Scott Pierpoint | 28 | Caucasian | Male | North Carolina | Child Sex Abuse | 1992 | 2010 |

| Jonathan Tears | 29 | Black | Male | Tennessee | Attempted Murder | 2009 | 2014 |

| Jonathan Wheeler-Whichard | 15 | Black | Male | New York | Murder | 1997 | 2009 |

| Jonathon Hoffman | 41 | Black | Male | North Carolina | Murder | 1996 | 2007 |

| Jorge Alvarez | 23 | Hispanic | Male | California | Manslaughter | 1996 | 2001 |

| Jose Caro | 27 | Hispanic | Male | Puerto Rico | Murder | 1994 | 2016 |

| Jose Garcia | 27 | Hispanic | Male | New York | Murder | 1993 | 2007 |

| Jose Luis Pena | 36 | Hispanic | Male | Texas | Drug Possession or Sale | 2003 | 2011 |

| Jose Montanez | 25 | Hispanic | Male | Illinois | Murder | 1994 | 2016 |

| Joseph Amrine | 28 | Black | Male | Missouri | Murder | 1986 | 2003 |

| Joseph Anthony Scamardo, Jr. | 35 | Caucasian | Male | Arkansas | Child Sex Abuse | 2010 | 2013 |

| Joseph Awe | 36 | Caucasian | Male | Wisconsin | Arson | 2007 | 2013 |

| Joseph Dick, Jr. | 20 | Caucasian | Male | Virginia | Murder | 1999 | 2016 |

| Joseph Eastridge | 28 | Caucasian | Male | District of Columbia | Murder | 1975 | 2005 |

| Joseph Green | 36 | Black | Male | Florida | Murder | 1993 | 2000 |

| Joseph Hoehmann | 35 | Caucasian | Male | New York | Child Sex Abuse | 1996 | 1998 |

| Joseph Salvati | 31 | Caucasian | Male | Massachusetts | Murder | 1968 | 2001 |

| Joseph Sledge | 34 | Black | Male | North Carolina | Murder | 1978 | 2015 |

| Joseph Smith | 32 | Caucasian | Male | New York | Murder | 2002 | 2002 |

| Joseph Sousa | 26 | Caucasian | Male | District of Columbia | Murder | 1975 | 2005 |

| Joseph White | 22 | Caucasian | Male | Nebraska | Murder | 1989 | 2008 |

| Joshua Kezer | 17 | Caucasian | Male | Missouri | Murder | 1994 | 2009 |

| Josiah Sutton | 16 | Black | Male | Texas | Sexual Assault | 1999 | 2004 |

| Joy Wosu | 33 | Black | Female | New York | Child Sex Abuse | 1993 | 2009 |

| Joyce Ann Brown | 33 | Black | Female | Texas | Murder | 1980 | 1990 |

| Juan Carlos Pichardo | 23 | Hispanic | Male | New York | Murder | 1994 | 2000 |

| Juan Celestino | 41 | Hispanic | Male | Ohio | Child Sex Abuse | 1991 | 1995 |

| Juan Herrera | 21 | Hispanic | Male | California | Murder | 1999 | 2006 |

| Juan Johnson | 19 | Black | Male | Illinois | Murder | 1991 | 2004 |

| Juan Ramirez-Lopez | 44 | Hispanic | Male | Fed-CA | Immigration | 2000 | 2003 |

| Juan Rivera | 19 | Hispanic | Male | Illinois | Murder | 1993 | 2012 |

| Juan Roberto Melendez | 32 | Hispanic | Male | Florida | Murder | 1984 | 2002 |

| Julie Rea | 28 | Caucasian | Female | Illinois | Murder | 2002 | 2006 |

| Julie Richardson | 44 | Caucasian | Female | California | Drug Possession or Sale | 1999 | 2001 |

| Justin Chapman | 27 | Caucasian | Male | Georgia | Murder | 2007 | 2016 |

| Justin Pacheco | 18 | Hispanic | Male | California | Murder | 1998 | 2000 |

| Kareem Bellamy | 26 | Black | Male | New York | Murder | 1995 | 2011 |

| Karen O'Dell | 37 | Caucasian | Female | Florida | Drug Possession or Sale | 1998 | 2000 |

| Karim Koubriti | 22 | Other | Male | Fed-MI | Supporting Terrorism | 2003 | 2004 |

| Kash Register | 18 | Black | Male | California | Murder | 1979 | 2013 |

| Kathryn Dawn Wilson | 22 | Caucasian | Female | North Carolina | Child Sex Abuse | 1993 | 1997 |

| Kathy Gonzalez | 24 | Hispanic | Female | Nebraska | Murder | 1989 | 2009 |

| Keevin Leonard | 42 | Caucasian | Male | Fed-NY | Fraud | 2009 | 2016 |

| Keith Cooper | 29 | Black | Male | Indiana | Robbery | 1997 | 2017 |

| Keith Harward | 26 | Caucasian | Male | Virginia | Murder | 1983 | 2016 |

| Keith Mitchell | 18 | Black | Male | District of Columbia | Murder | 1994 | 2015 |

| Kelvin Wiley | 29 | Black | Male | California | Assault | 1990 | 1992 |

| Kennedy Brewer | 21 | Black | Male | Mississippi | Murder | 1995 | 2008 |

| Kenneth Adams | 21 | Black | Male | Illinois | Murder | 1978 | 1996 |

| Kenneth Atkins | 16 | Caucasian | Male | Florida | Sexual Assault | 2004 | 2008 |

| Kenneth Conley | 27 | Caucasian | Male | Massachusetts | Perjury | 1998 | 2005 |

| Kenneth Faulkner | 39 | Caucasian | Male | California | Kidnapping | 2000 | 2003 |

| Kenneth Gordon | 40 | Black | Male | Illinois | Theft | 2002 | 2008 |

| Kenneth Ireland | 16 | Caucasian | Male | Connecticut | Murder | 1989 | 2009 |

| Kenneth Kagonyera | 20 | Black | Male | North Carolina | Murder | 2001 | 2011 |

| Kenneth Pavel | 41 | Caucasian | Male | New York | Child Sex Abuse | 1989 | 2001 |

| Kenneth Waters | 25 | Caucasian | Male | Massachusetts | Murder | 1983 | 2001 |

| Kenneth Wayne Boyd, Jr. | 22 | Black | Male | Texas | Murder | 1999 | 2013 |

| Kerry Kotler | 22 | Caucasian | Male | New York | Sexual Assault | 1982 | 1992 |

| Kerry Porter | 34 | Black | Male | Kentucky | Murder | 1998 | 2011 |

| Kevin Baruxes | 18 | Caucasian | Male | California | Sexual Assault | 1996 | 2003 |

| Kevin K. Peterson | 33 | Caucasian | Male | Nebraska | Murder | 1994 | 1995 |

| Kevin Martin | 17 | Black | Male | District of Columbia | Manslaughter | 1984 | 2014 |

| Kevin Pease | 19 | Native American | Male | Alaska | Murder | 1999 | 2015 |

| Kevin Peterson | 32 | Caucasian | Male | Utah | Child Sex Abuse | 1990 | 2012 |

| Kevin Richardson | 14 | Black | Male | New York | Sexual Assault | 1990 | 2002 |

| Kevin Siehl | 35 | Caucasian | Male | Pennsylvania | Murder | 1992 | 2016 |

| Kian Khatibi | 22 | Caucasian | Male | New York | Assault | 1999 | 2008 |

| Kim Hairston | 32 | Black | Male | Ohio | Murder | 1993 | 1995 |

| Kimberly Mawson | 32 | Caucasian | Female | Rhode Island | Murder | 2007 | 2012 |

| Korey Wise | 16 | Black | Male | New York | Sexual Assault | 1990 | 2002 |

| Kristie Mayhugh | 21 | Hispanic | Female | Texas | Child Sex Abuse | 1998 | 2016 |

| Kristine Bunch | 21 | Caucasian | Female | Indiana | Murder | 1996 | 2012 |

| Kum Yet Cheung | 29 | Asian | Male | California | Attempt, Violent | 1995 | 2002 |

| Kwame Ajamu | 17 | Black | Male | Ohio | Murder | 1975 | 2014 |

| Kyle Weldon | 21 | Caucasian | Male | Iowa | Drug Possession or Sale | 2015 | 2017 |

| Lafayette Green | 38 | Black | Male | Florida | Sexual Assault | 1996 | 1997 |

| Lambert Charles | 16 | Black | Male | New York | Manslaughter | 1993 | 1998 |

| Lamont Branch | 23 | Black | Male | New York | Murder | 1990 | 2002 |

| LaMonte Armstrong | 38 | Black | Male | North Carolina | Murder | 1995 | 2013 |

| Lana Canen | 43 | Caucasian | Female | Indiana | Murder | 2005 | 2012 |

| Larod Styles | 16 | Black | Male | Illinois | Murder | 1998 | 2017 |

| Larry Bostic | 31 | Black | Male | Florida | Sexual Assault | 1989 | 2007 |

| Larry Delmore | 22 | Black | Male | Louisiana | Murder | 1993 | 2010 |

| Larry Gurley | 20 | Black | Male | New York | Murder | 1972 | 1994 |

| Larry Hudson | 19 | Black | Male | Louisiana | Murder | 1967 | 1993 |

| Larry Lamb | 36 | Black | Male | North Carolina | Murder | 1993 | 2013 |

| Larry Lane Hugee | 48 | Black | Male | Maryland | Robbery | 2004 | 2013 |

| Larry Ollins | 16 | Black | Male | Illinois | Murder | 1988 | 2001 |

| Larry Osborne | 17 | Caucasian | Male | Kentucky | Murder | 1999 | 2002 |

| Larry Pat Souter | 26 | Caucasian | Male | Michigan | Murder | 1992 | 2005 |

| Larry Peterson | 36 | Black | Male | New Jersey | Murder | 1989 | 2006 |

| Larry Pohlschneider | 33 | Caucasian | Male | California | Child Sex Abuse | 2001 | 2015 |

| Larry Ruffin | 19 | Black | Male | Mississippi | Murder | 1980 | 2011 |

| Larry Williams, Jr. | 16 | Black | Male | North Carolina | Murder | 2002 | 2015 |

| Lashane Westbrooks | 29 | Black | Male | New York | Drug Possession or Sale | 2007 | 2007 |

| LaShawn Ezell | 15 | Black | Male | Illinois | Robbery | 1998 | 2017 |

| LaShawn Johnson | 28 | Black | Male | Fed-MT | Drug Possession or Sale | 2006 | 2015 |

| Lathan Word | 18 | Black | Male | Georgia | Robbery | 2000 | 2011 |

| Lathierial Boyd | 24 | Black | Male | Illinois | Murder | 1990 | 2013 |

| Latisha Johnson | 18 | Black | Female | New York | Attempted Murder | 2007 | 2014 |

| Laurence Adams | 19 | Black | Male | Massachusetts | Murder | 1974 | 2004 |

| Laurie Moore | 33 | Caucasian | Male | Michigan | Manslaughter | 1987 | 1991 |

| Lavell Jones | 19 | Black | Male | New York | Murder | 1999 | 2016 |

| LaVelle Davis | 20 | Black | Male | Illinois | Murder | 1997 | 2009 |

| Lawrence Simmons | 19 | Black | Male | New Jersey | Murder | 1977 | 2000 |

| Lazaro Burt | 20 | Black | Male | New York | Murder | 1994 | 2002 |

| Lee Keifer | 25 | Caucasian | Male | Oklahoma | Child Sex Abuse | 1993 | 1997 |

| Leon Brown | 15 | Black | Male | North Carolina | Murder | 1984 | 2014 |

| Leonard Craine | 37 | Black | Male | Nevada | Child Sex Abuse | 1990 | 2002 |

| Leroy Orange | 32 | Black | Male | Illinois | Murder | 1985 | 2003 |

| Les Burns | 32 | Caucasian | Male | Fed-VA | Drug Possession or Sale | 2014 | 2016 |

| Levon Brooks | 26 | Black | Male | Mississippi | Murder | 1992 | 2008 |

| Levon Jones | 28 | Black | Male | North Carolina | Murder | 1993 | 2008 |

| Lewis Fogle | 24 | Caucasian | Male | Pennsylvania | Murder | 1982 | 2015 |

| Lewis Gardner | 15 | Black | Male | Illinois | Murder | 1995 | 2014 |

| Lewis Hagan | 38 | Black | Male | New Jersey | Child Sex Abuse | 2004 | 2010 |

| Linus Nwaigwe | 45 | Black | Male | Fed-NY | Fraud | 2009 | 2015 |

| Lionel Lane | 33 | Black | Male | Illinois | Murder | 1995 | 1995 |

| Lionel White | 33 | Black | Male | Illinois | Drug Possession or Sale | 2006 | 2016 |

| Lon Walker | 43 | Caucasian | Male | Tennessee | Murder | 1997 | 2012 |

| Lonnie Jones | 34 | Black | Male | New York | Murder | 2002 | 2007 |

| Lorenzo Montoya | 14 | Hispanic | Male | Colorado | Murder | 2000 | 2014 |

| Lorinda Swain | 36 | Caucasian | Female | Michigan | Child Sex Abuse | 2002 | 2016 |

| Louis Eze | 31 | Black | Male | New York | Child Sex Abuse | 1993 | 2007 |

| Louis Greco | 47 | Caucasian | Male | Massachusetts | Murder | 1968 | 2001 |

| Luis Davalos | 16 | Hispanic | Male | California | Manslaughter | 1996 | 2001 |

| Luis Galicia | 21 | Hispanic | Male | California | Child Sex Abuse | 2008 | 2011 |

| Luis Ortiz | 18 | Hispanic | Male | Illinois | Murder | 2000 | 2003 |

| Luis Santaliz Acosta | 34 | Hispanic | Male | Puerto Rico | Murder | 2000 | 2009 |

| Lumont Johnson | 29 | Black | Male | Illinois | Murder | 2002 | 2015 |

| Luther Jones, Jr. | 50 | Black | Male | California | Child Sex Abuse | 1998 | 2016 |

| Lydia Salce | 50 | Caucasian | Female | New York | Attempted Murder | 2012 | 2015 |

| Lynie Gaines | 36 | Black | Male | Michigan | Drug Possession or Sale | 1990 | 1997 |

| Lynn DeJac | 30 | Caucasian | Female | New York | Murder | 1994 | 2008 |

| M. Donald Cardwell | 63 | Caucasian | Male | Fed-CT | Tax Evasion/Fraud | 2000 | 2000 |

| MacArthur Campbell | 40 | Black | Male | New Mexico | Child Sex Abuse | 2003 | 2008 |

| Madison Hobley | 26 | Black | Male | Illinois | Murder | 1990 | 2003 |

| Malcolm Emory | 19 | Native American | Male | Massachusetts | Assault | 1970 | 1990 |

| Malcolm Scott | 17 | Black | Male | Oklahoma | Murder | 1995 | 2016 |

| Malisha Blyden | 22 | Black | Female | New York | Attempted Murder | 2007 | 2014 |

| Manual Hidalgo Rodriguez | 36 | Hispanic | Male | Washington | Child Sex Abuse | 1995 | 2000 |

| Marcella Pitts | 29 | Caucasian | Female | California | Child Sex Abuse | 1985 | 1991 |

| Marcellius Bradford | 17 | Black | Male | Illinois | Kidnapping | 1988 | 2001 |